Download pdf: Why maintain soil reserves (1.91M)

pdf 1.91M

Why maintain soil reserves

December 2025

The arable sector is facing challenging conditions as the impact of the last few years weather brought lower than average yields for many last harvest, whilst prices for most commodities are far from where they need to be. Added to this is the reduction in government support, a lack of certainty surrounding future environmental support and the much-criticised changes to inheritance tax changes affecting the industry as a whole.

In such challenging financial times, it can almost seem quite flippant to discuss the maintenance of soil nutrient reserves. Even the use of the word reserves conjures up ideas of excess; over supply; a pot to tap into when times are tough; however for phosphate and potash this is not the case.

Crop demand – quantity and rate

Crops take up very different amounts of P&K during growth, but they all need a readily available supply in the soil at key times during the season. For potatoes, two-thirds of the potash requirement is taken up in the six weeks after plant emergence. For winter cereals a small amount of phosphate and potash are needed for establishment, but most is taken up in the period between tillering and ear emergence, during canopy expansion (figure 1).

In periods of rapid growth crops can take up as much as 10 kg K2O/ha each day from the soil solution. With such large daily requirements, soils need to be well supplied with nutrient to allow for these levels to be released from exchange sites (clay particles and organic matter).

Research at Rothamsted through the 1960s and 70s showed that, on many soils, potash reserves accumulated from applications of fertilisers and organic manures increased crop yields compared to those obtained on similar soils but without such reserves.

However, there is no need to continually build up reserves. Yields of crops will follow the Law of Diminishing Returns, that is, as exchangeable P&K in soil increases then yield will increase rapidly at first and then more slowly until it reaches a maximum beyond which there is no further increase in yield despite further increases in exchangeable P&K reserves.

The indices at which yield approaches close to the maximum can be considered the critical value. Below the critical value the loss of yield is a financial loss to the farmer. Above the critical value, there is no justification for further increase in the available P or K because this is an unnecessary expense.

Current recommendations for phosphate and potash on arable soils are to maintain the soil at P Index 2 and K Index 2- for most crops and at P Index 3 and K Index 2+ for potatoes and vegetables. Thus, if the crop rotation on an individual field includes potatoes and/or vegetables the soil should be maintained at these higher indices. This is because the phosphate and potash fertilisation policy should apply to the whole rotation of crops on the farm and it is most important to maintain soil fertility for the rotation. Once the soil has been brought to the appropriate index for the rotation it should be maintained by replacing the amount of P&K removed in the harvested crop.

The last 40 years has seen a decline in phosphate and potash fertiliser inputs, to the point that most arable crops are now in a nutrient balance deficit (see charts below). Even accounting for the input from manures, this declining use will have an adverse effect on soil fertility and on the production of economically viable crop yields of acceptable quality.

Maintaining soil fertility to produce economically viable yields requires the appropriate use of all inputs including plant nutrients. A current danger is reducing phosphate and potash inputs to save money, but this can be very short sighted, helping cash flow at the expense of capital value loss, yield and potentially flouting the terms of rental agreements.

Saving money on phosphate and potash applications might be possible if the soil happens to contain large reserves of P and K in the less-readily available pool or a large amount of clay that releases potassium. But what are the risks and consequences if these assumptions are wrong?

The rate of decline in readily plant-available soil P or K (determined in the laboratory) will depend on the initial value, the amount of nutrients removed in the harvested crop, and the size and rate of transfer of reserves from the less-readily available pool. Experiments suggest that a good ‘rule of thumb’ is that the exchangeable K will halve in 10 years when no potash fertiliser is applied, in a combinable crop rotation.

Thus, it could take 10 years to go from the top of K Index 1 to the top of K Index 0.

Effects of declining levels of yield

Farmers are unlikely to see a decline in yields in the first few years of not applying potash to arable land at or above the critical index of 2-. This is because of:

- replenishment from reserves;

- seasonal variation in yields, caused by differences in the weather and the incidence of pests and diseases that change the amount of K taken off in the harvested produce;

- effects of soil cultivation and uptake of some K from the subsoil by deep-rooted crops like winter wheat and sugar beet.

In the longer-term declining soil K will inevitably result in declining yields. This has been demonstrated many times in long-term field experiments at Rothamsted and elsewhere.

The biggest effects are seen in those crops that need most phosphate and potash or have poor root systems which are unable to exploit soil reserves effectively, such as potatoes or beans.

Where soils have been left to fall below the target index, applying fresh P or K fertiliser did not increase crop yields to equal those obtained on a soil with an adequate amount of available nutrient. Trials carried out on multiple crops have shown this to be the case:

Other effects of declining levels

Loss of yield is not the only result of potash deficiency in soil. Lack of potash results in:

- inefficient use of other nutrients, especially nitrogen, a financial cost to the farmer with the risk of environmental pollution through nitrate leaching and emissions of nitrous oxide;

- enhanced susceptibility to crop diseases and the likely need to increase pesticide use – more cost and more risk of pollution;

- less natural vigour and resistance to stress from pests, diseases and adverse weather;

- weaker straw with greater risk of lodging;

- reduced grain quality.

The decrease in yields with declining exchangeable K in long-term experiments also emphasise the importance of balanced nutrition – that is maintaining the supply of adequate amounts of all nutrients. Balanced nutrition involving N x P x K x S interactions needs to be more fully appreciated and responded to by those wishing to achieve optimum economic yields of good quality produce. The yields of winter wheat in the trials carried out by Yara in 2018 (Figure 6) show the greatest yield was achieved where the proper supply of macro and micronutrients in a balanced ratio supplied throughout the growth of the crop. The omission of any one of these nutrients led to a reduction in yield.

Cost of rebuilding reserves

There is not much research upon which to base a calculation of the costs of rebuilding nutrient reserves if they fall below the critical level. Again, the long-term experiments at Rothamsted provide the best basis. Taking into account the movement of potash from ‘Readily Available’ into ‘Less Readily Available’ forms during build up, but ignoring crop removals, researchers found that it took 10 kg K2O/ ha in excess of crop requirements to increase the exchangeable soil K by 1 mg/kg. It would therefore require an application of potash in excess of normal crop requirements of approximately 600 kg K2O/ha to move from the middle of Index 1 to Index 2- and 1200 kg K2O/ha to move from the middle of Index 0 to 2-. And similarly, maybe 450 and 900 kg P2O5/ ha respectively for phosphate.

The practical conclusion to be drawn from this is not to allow soil P&K to fall below target levels and this is further endorsed by consideration of the crop value penalties involved.

However, it is not recommended to restore low soil nutrient levels with such large quantities in a single year. Besides the cost of buying and applying such large amounts of P&K fertiliser there is a risk that unless the fertiliser is applied at the right time and is very well mixed into the cultivated soil there could be a serious risk of ‘salt’ damage to germinating seedlings and increased loss to the environment, particularly problematic for phosphate.

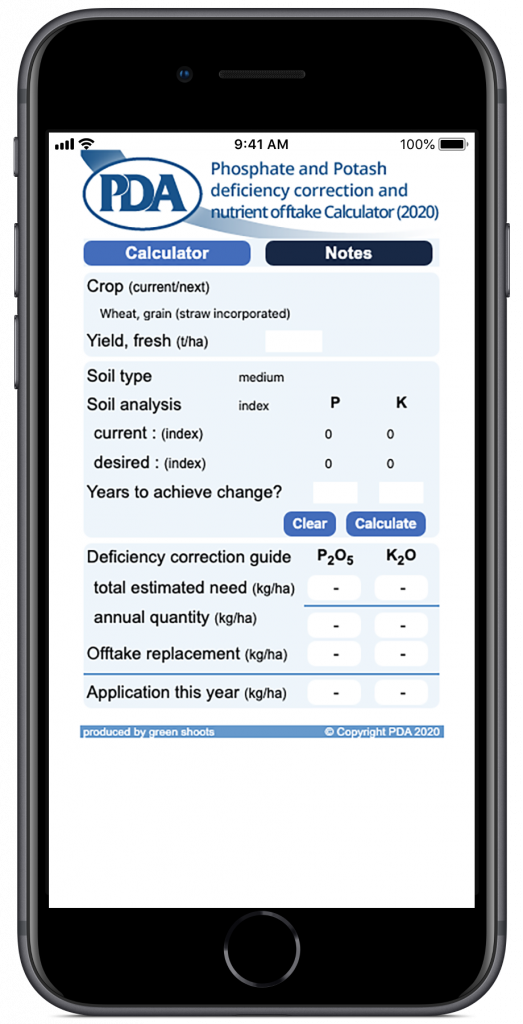

PDA PK Calculator

The PDA PK Calculator was designed to give flexibility to the calculation of building up soil reserves by allowing the timescale over which it is targeted to be entered. It provides both an annual figure, including replacing the offtake of the crop grown in that season, as well as the total requirement for the period selected.

Claim your CPD Points for 2025/26

BASIS Professional Register: claim your points by e-mailing cpd@basis-reg.co.uk for year ending 31st May 2026 quoting reference:

Potash News – 205496063191

PDA Membership – 217362414796

NRoSO: claim 2 points by e-mailing nroso@basis-reg.co.uk for year ending 31st August 2026 quoting reference: NO505967f